Growth Plate Fractures

The bones of children and adults share many of the same risks for injury. However, a child's bones are also subject to a unique injury called a growth plate fracture.

Approximately 15% to 30% of all childhood fractures are growth plate fractures. These often require immediate attention because the long-term consequences may include limbs that are crooked or of unequal length.

Although growth plate injuries are common, serious problems are rare. Growth deformity occurs in 1% to 10% of all growth plate injuries.

Appropriate evaluation by an orthopaedic surgeon experienced in orthopaedic trauma will determine the nature of the growth plate injury, will provide counseling about treatment options, and will allow for longer term follow up to assess the outcome of the injuries.

What is a growth plate?

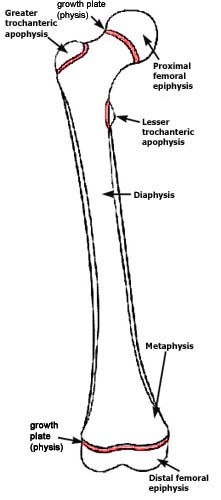

The growth plate (physis) is an area of developing tissue near the ends of long bones, between the widened part of the shaft of the bone (the metaphysis) and the end of the bone (the epiphysis). The growth plate regulates and helps determine the length and shape of the mature bone.

The long bones of the body do not grow from the center outward. Instead, growth occurs at each end of the bone around the growth plate. The growth plate is the last portion of the bone to harden (ossify), which leaves it vulnerable to fracture. Because muscles and bones develop at different speeds, a child's bones may be weaker than the surrounding connective tissues (ligaments).

Children's bones heal faster than adult's bones. This has two important consequences. First, it means that a child with an injury should see a doctor as quickly as possible, so the bone gets the proper treatment before it begins to heal. Ideally, this means seeing an orthopaedic specialist within five to seven days of the injury, especially if manipulation to align the bone is required. Second, the period of immobilization required for healing will not be as long as for an adult.

To make the diagnosis, the doctor will examine the child and probably use X-rays to determine whether a growth plate fracture occurred. Occasionally, the doctor may request other diagnostic tests, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomography (CT), or ultrasound.

Cause

Fractures can result from a single traumatic event, such as a fall or automobile accident, or from chronic stress and overuse.

Most growth plate fractures -- more than 30% -- occur in the long bones of the fingers. They are also common in the the outer bone of the forearm (radius), and lower bones of the leg (the tibia and fibula).

Who is at risk?

- All children who are still growing are at risk for a growth plate injury. These injuries are reported to peak in adolescents.

- Growth plate fractures occur twice as often in boys as in girls.

- One third of all growth plate injuries occur in competitive sports, such as football, basketball, or gymnastics.

- About 20 percent of growth plate fractures occur as a result of recreational activities, such as biking, sledding, skiing, or skateboarding.

Symptoms

Any child who experiences an injury that results in visible deformity, persistent or severe pain, or an inability to move or put pressure on a limb should be examined by a doctor.

Treatment

Growth plate fractures are classified depending on the degree of damage to the growth plate itself. Treatment depends on the fracture type.

Several classification systems of growth plate fractures have been developed. Perhaps the most widely used is the Salter-Harris system. The more recent Peterson classification better describes all growth plate fracture problems.

In addition, there are other factors that may affect the bone growth and fracture healing. These include such things as the age and health of the patient, associated injuries, and the amount of displacement of the fractured ends of the bone (occuring through the growth plates).

The following section describes the different types of growth plate fractures.

Type I Fractures

These fractures break the bone through the growth plate, but no shift of the bone occurs. The fracture is often not visible on an X-ray.

- They generally heal well. The bone remains aligned and usually no surgery is required.

- They are treated by cast immobilization.

Type II Fractures

These fractures break through part of the bone at the growth plate and crack through the bone shaft as well.

- These fractures generally heal well, although surgery may sometimes be required. This is the most common type of growth plate fracture.

- Most are treated with cast immobilization.

Type III Fractures

These fractures break through the bone at the growth plate, separating the bone end from the bone shaft and completely disrupting the growth plate.

- May result in arrested growth and requires surgical treatment.

- Often treated with internal fixation to ensure proper alignment.

Type IV Fractures

These fractures cross through a portion of the growth plate and break off a piece of the bone end.

- These fractures are more common in older children. Because the center of the growth plate has begun to harden, the fracture does not continue across the bone, but angles down and breaks the bone end.

- It is treated with surgery and internal fixation to ensure proper alignment of both the growth plate and the joint surface.

Type V Fractures

These fractures break through the bone shaft, the growth plate, and the end of the bone.

- They commonly result in arrested growth of the bone.

- They are treated with surgery and internal fixation.

Type VI Fractures

These fractures are similar to type V fractures, but the broken pieces of bone are missing. These fractures may involve lawnmowers, farm machinery, or gunshot wounds.

- They occur only with fractures that break the skin (open) or have multiple breaks (comminuted).

- They require initial surgery for repair and fixation. Additional reconstructive or corrective surgery may also be needed.

Results

Growth plate fractures must be watched carefully to ensure proper long-term results. In some cases, a bony bridge will form that prevents the bone from getting longer or will cause a curve of the bone. Orthopaedic surgeons are developing techniques that enable them to remove the bony bar and insert fat, cartilage, or other materials to prevent it from reforming.

In other cases, the fracture actually stimulates growth so that the injured bone is longer than the uninjured bone. Surgical techniques can help achieve more even length.

Regular follow-up visits to the doctor should continue for at least a year after the fracture. Complicated fractures (types IV, V, and VI) as well as fractures to the thighbone (femur) and shinbone (tibia) may need to be followed until the child reaches skeletal maturity.

Reviewed by members of POSNA (Pediatric Orthopaedic Society of North America)

copy.jpg)